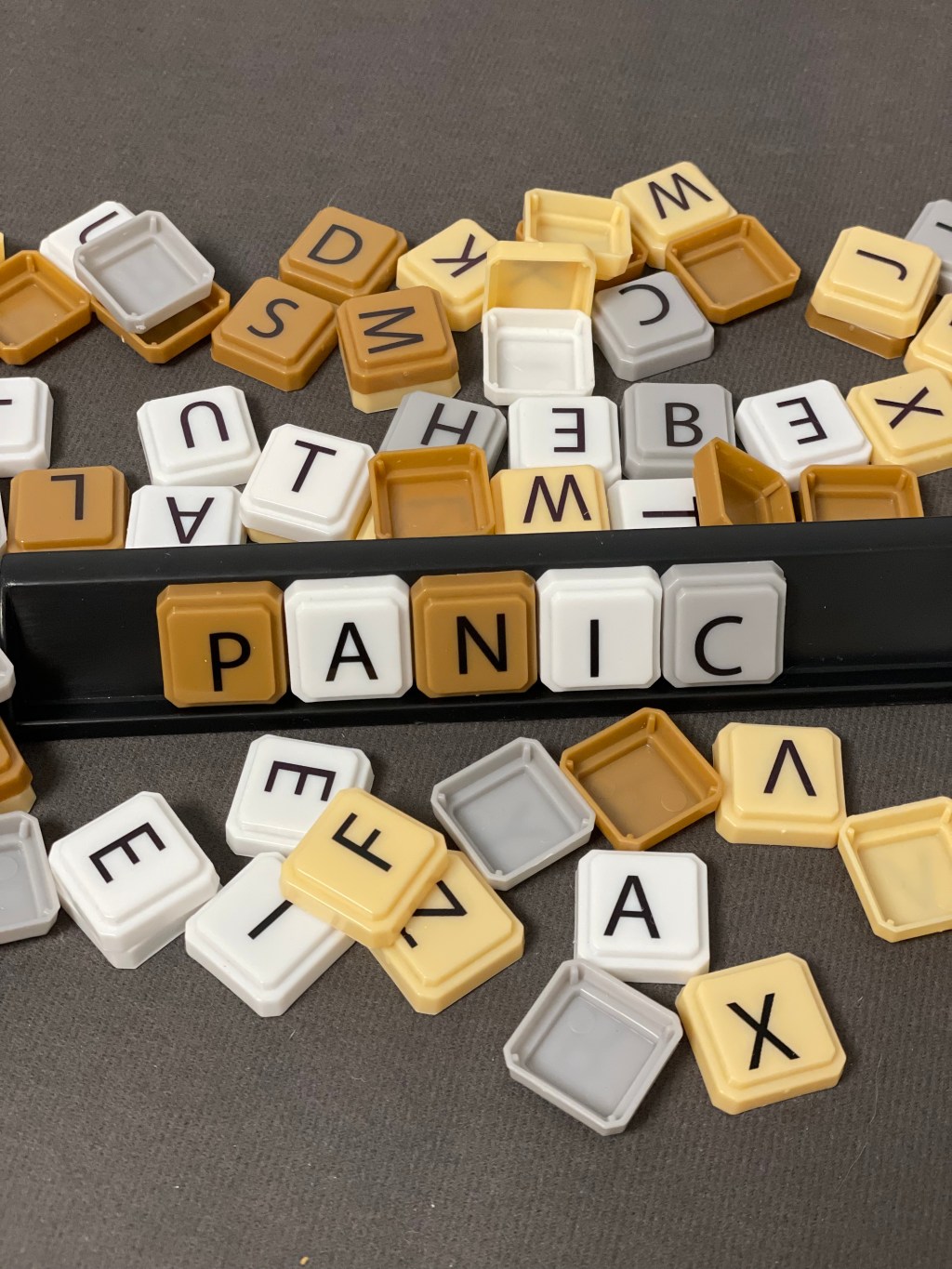

A panic attack, by definition, is “a sudden episode of intense fear or anxiety and physical symptoms, based on a perceived threat rather than imminent danger.”

It’s not wrong, but it’s incomplete.

For those of us who live with them, panic attacks feel deeply personal—custom-tailored to amplify our worst fears. Sometimes those fears are buried so deep, we didn’t even know they existed. Panic gives those fears a voice. A body.

Reading the definition might help you name the experience, but it doesn’t dull the impact. It doesn’t stop the awful, paralyzing sensations. In the middle of it, rational thought becomes useless, and as impossible as it sounds, you just have to ride it out and hope you survive. At least, that’s what it was like for me—especially in the beginning.

I’ve been having panic attacks for as long as I can remember. I think they started in my early teens. Back then, I didn’t have language for what was happening—I just knew something felt wrong. The terror would strike out of nowhere. Sudden. Disorienting. All-consuming.

For years, I thought I was losing my mind and was afraid I’d eventually be institutionalized. That became one of my greatest fears—not the attacks themselves, but what they might do to me. That I’d stay frozen in that place forever. That I’d lose my grip on reality.

It wasn’t until my late twenties, after a string of personal losses and one particularly devastating episode, that I finally learned what I was dealing with: panic disorder. The diagnosis brought unexpected relief. I wasn’t crazy. I wasn’t broken. I was having panic attacks—something real. Something explainable.

But even with the knowledge of that, I lived in fear of the day I was certain would break me: the day I lost my mom.

She had been struggling with her health for a long time, and I carried the anticipation of her death like a weight strapped to my chest. I pictured the worst panic attack of my life—imagined it would destroy me completely.

When panic hits, it hits me hard. It’s a full-body dissociation—an out-of-body experience. I can see myself, but I’m not in myself. Time fractures, like the world has broken into disconnected frames. My limbs go numb. My body locks up. I become untethered, swallowed by something invisible. This kind of panic was terrifying on its own—I could only imagine what it would do to me when my mother died.

Looking back, I can see that my body was always trying to protect me. In its own distorted way, panic was my nervous system’s desperate attempt at control. And control became my survival strategy.

I coped through superstition, rituals, routines, regimens. I craved sameness and predictability. The unknown scared me. Things I couldn’t control—like flying—left me paralyzed. Not enough to stop me, but enough to rob me of peace.

Eventually I went looking for the root of it all. I wanted to understand why. Why my body turned to panic. Why I couldn’t just be “normal.”

The answer was painfully simple: I hadn’t learned it was okay to be me.

I was always different from my family. I felt things more deeply. I asked too many questions and never settled for easy answers. I was both curious and cautious—always needing to understand why. And when I couldn’t, it left me unsteady, like the ground had shifted beneath me. The internet would’ve been a lifeline back then. Encyclopedias and books couldn’t keep up with how urgently I needed answers.

The version of “normal” I grew up around never felt right. I tried so hard to fit in, to become who I thought I was supposed to be. The idea that I might never manage it—that I might always feel like an outsider—was overwhelming. It made the world feel unsafe. I didn’t know how to put all of this into words.

But my body knew. And it spoke through panic.

Once I had a name for what was happening, I did everything I could to avoid it. I planned. I prepared. I micromanaged my life. But avoidance only made things worse. Panic feeds on fear—and fear thrived on my efforts to keep it away.

I realized I had to stop running. I had to face it. Acknowledge it. Learn how to live with it.

Finally, through therapy and self-work, I’ve learned to recognize the signs. I’ve learned how to talk to the panic when it comes. I’m not as afraid of it anymore. I coach myself through it: Okay. We’re okay. Just move. Just breathe. YOU. ARE. SAFE.

It sounds simple, but it’s not. It takes everything I have. And when it passes, I’m exhausted—drained for the rest of the day. But I’ve made progress. The attacks come less often now. They’re shorter. Softer. More manageable.

When it happened—when my mother died—panic spared me.

I don’t know why. Maybe the universe knew I’d reached my limit. Maybe the years of waiting for the worst were the source of my anxiety all along. Because when she was gone, there was nothing left to fear. Just stillness. Just grief.

And when I miss her the most—her voice, her warmth, her love—when I grieve not just what I lost, but what my son will never know, what her dog still waits for, what the world feels like without her light…panic still doesn’t come.

I used to think that panic would be the thing that undid me. But grief, as crushing as it is, doesn’t leave room for panic. It demands presence. Feeling.

Maybe that’s the difference. Grief and panic don’t always coexist. Panic floods in when we try not to feel or are too afraid to. And grief is feeling. All of it. So in the fullness of feeling, panic stays quiet.

The stillness didn’t last. But while it was here, it taught me something I hadn’t understood before: panic doesn’t always show up when you expect it. And sometimes, surviving your worst fear can bring unexpected peace.

Panic hasn’t disappeared. It still shows up, uninvited—tapping me on the shoulder from time to time, reminding me to feel. I don’t always listen, but I know what it wants now. I know its shape. I can talk to it like an old unwelcome friend. I can look it in the eye—not with comfort, but with clarity.

Leave a comment